Grammar

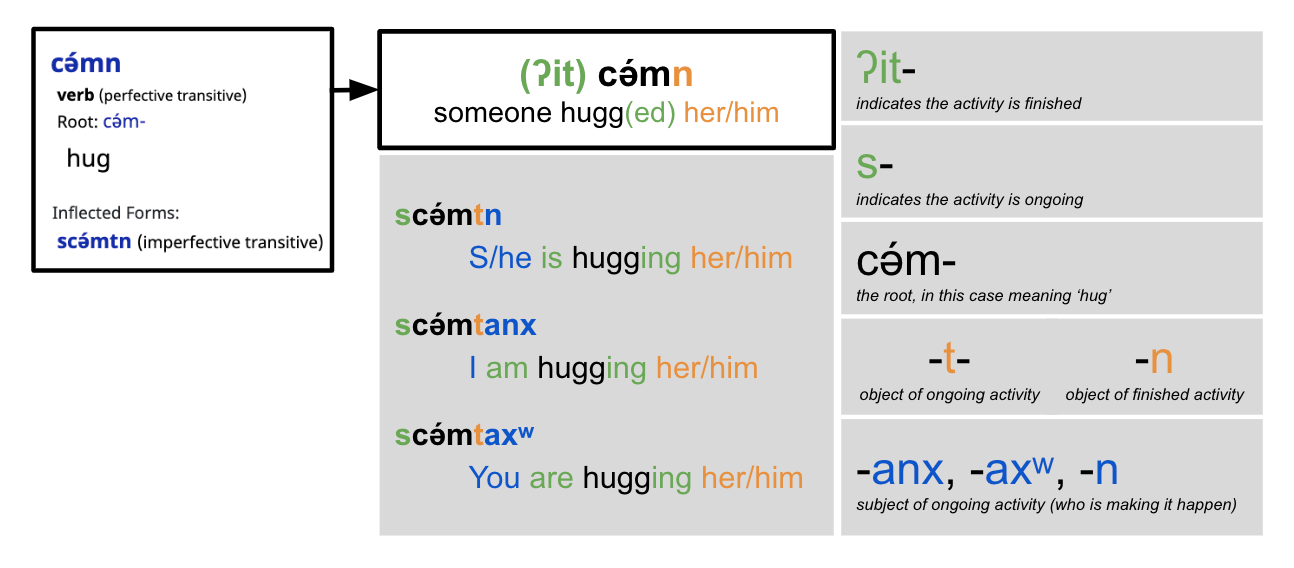

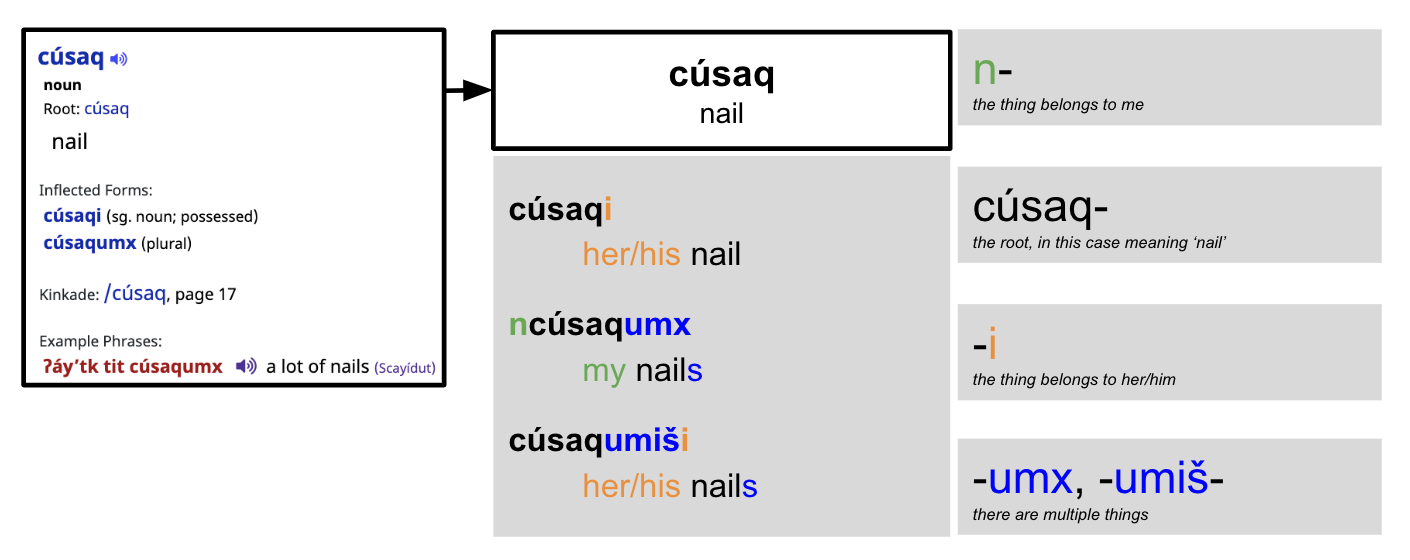

The Cowlitz Coast Salish language is very different from English. An entire English sentence can translate to a single Cowlitz word, made up of many different pieces. To express a specific idea, you will have to arrange these parts in a particular way.

In the dictionary, only one form can be listed as the main headword. Verb entries generally take the same form as one another, and noun entries generally take the same form as one another. Below are examples of typical dictionary entry forms and how you would use the entry to express various ideas.

Finally, not all entries in this dictionary are equally reliable. Consider all options carefully when choosing a translation, and when in doubt look over the example phrases and entry notes.

Lexical Suffixes

Lexical Suffix Definition

Lexical suffixes are a set of morphemes that are frequently used to derive new words from existing roots. Like most roots, lexical suffixes can never be used as a full word on their own. Many English words and phrases translate into Cowlitz Coast Salish as a root or stem with a lexical suffix attached. Below is a list of example words composed of a root and a lexical suffix. In these examples, the lexical suffixes are marked with an equals sign ( = ) in front. In this dictionary, you’ll typically see them without equals signs, but that formatting may be subject to change.

| Ex: | ʔáwtičn | a person’s back, behind | [ √ʔáwat- ‘behind’ + =ikn ‘back’ ] |

| táwʼkʷu | high water, flowing water | [ √táwʼ- ‘big’ + =kʷu ‘water’ ] | |

| qʼáxʷakaʔ | frostbitten hands | [ √qʼáxʷa- ‘freeze’ + =akaʔ ‘hand’ ] | |

| x̣wíʔičn | backbone | [ √x̣wiʔ- ‘bone’ + =ikn ‘back’ ] |

Did you notice that the lexical suffix for ‘back,’ =ikn, has a different form in the morpheme breakdowns than in the actual words? Sometimes, a lexical suffix will take a different form depending on the word it’s in.

Adding a lexical suffix to a root often creates a word with a different part of speech from the root by itself. In the examples above, √qʼáxʷa- is a verbal root meaning ‘freeze,’ and adding the lexical suffix =akaʔ to it creates a noun that means ‘frostbitten hands.’ √táwʼ- is an adjectival root meaning ‘big,’ and combining it with the lexical suffix =kʷu ‘water’ creates a noun meaning ‘high water.’

A key feature of lexical suffixes is that most of them have corresponding standalone words, which are discussed in the next section.

Standalone Counterpart Words

The phrase “standalone counterpart” refers to words that have the same meaning as a lexical suffix, but can be used on their own. You may find that many root + lexical suffix words can often also be written out as phrases containing their standalone counterpart words, and vice versa. This is especially true of lexical suffixes used with number roots. The following table contains a list of root + lexical suffix words and their respective full phrases. In this table, the lexical suffixes are written as they appear in the word rather than in their base form.

| Root + Lexical Suffix | Full Phrase |

|---|---|

| cámʼxawʼɬ ‘two rows’ [ √cám- ‘two’ + =xawʼɬ ‘row’ ] |

sáliʔ t xə́wɬ ‘two rows’ [ sáliʔ ‘two’ + t ‘a/an/the’ + xə́wɬ ‘row’ ] |

| cámuslʼs ‘eight dollars’ [ √cámus ‘eight’ + =l’s ‘dollar’ ] |

cámus t tála ‘eight dollars’ [ cámus ‘eight’ + t ‘a/an/the’ + tála ‘money’ ] |

| ʔaksqʷúx̣ʷlʼwltxʷ ‘white house’ [ ʔaks- ‘color/kind’ + √qʷúx̣ʷ- ‘white’ + =lwltxʷ ‘house’ ] |

ʔaksqʷúx̣ʷ t x̣áx ‘white house’ [ ʔaksqʷúx̣ʷ ‘white’ + t ‘a/an/the’ + x̣áx ‘house’ ] |

Some lexical suffixes bear a resemblance to their standalone counterparts:

| English |

Cowlitz Coast Salish standalone word |

Cowlitz Coast Salish lexical suffix |

|---|---|---|

| nose | mə́qsn | =qs |

| fire, firewood | mə́kʷp | =kʷup- |

| prairie | máqʷm | =aqʷ-, =aqʷm- |

| face | cmús | =us- |

| earth | tə́mx | =tmax- |

Many of them do not resemble their full word counterparts:

| English |

Cowlitz Coast Salish standalone word |

Cowlitz Coast Salish lexical suffix |

|---|---|---|

| basket | ʔə́mx̣kʷu | =ikn- |

| back | yax̣álʔ | =ikn- |

| water | qálʔ | =kʷu- |

| fire | mə́kʷp | =staq |

| wood | kʷúmɬ | =kʷup |

| together | x̣ʷúqʷɬ | =álʼwas- |

| hand | kálx | =akaʔ- |

| arm | kálx | =áx̣an- |

| foot | cúɬ | =xan- |

| leg | cúɬ | =ayaq- |

| child, offspring | mánʔ | =iʔɬ |

| face | cmús | =alis-, =lʼs |

| mouth | qə́nx | =ɬanal- |

| hair | kʼə́skʼs | =aqan- |

| heart, mind | sqʷə́lm | =ínwat- |

| stomach, belly | kʼʷásn | =ínwas- |

| neck | kʼə́spn | =apsam- |

| people | sxamʼálaxʷ | =mix- |

| animal | pə́saʔ | =ayuʔ- |

| ten | pánačš | =tumx |

| year | sƛʼíx | =panxʷ |

To make finding related words easier, we've put lists of words derived from a lexical suffix in the entry for that suffix’s corresponding standalone word.

Lexical Suffix Linking Letters

Youʼll often see a linking letter or two used between a root and a lexical suffix. The function of some of these is still unclear, but we think many of them are used to make pronunciation a little easier. The usual shape of the linking letters are: -al-, -ɬ-, -ay-, and -l-.

| Ex: | cʼəwə́kʼ- 'cut' + -ay- 'linking letter' + =kʷup- 'fire, firewood' → cʼukʼáykʷp 'chop wood' |

Lexical Suffixes and Numbers

Numbers are unique in that some of them use a different root shape when combining with a lexical suffix:

| English |

Cowlitz Coast Salish standalone word |

Cowlitz Coast Salish compounding form |

|---|---|---|

| one | ʔúcʼs | nákʼ- |

| two | sáliʔ | cám- |

| three | káʔɬiʔ | kán- |

| four | mús | mús- |

| five | čílačš | cílks-, cílkst- |

| six | tʼax̣ə́m | tʼə́x̣m- |

| seven | cʼóps | cʼúps-, cʼóps- |

| eight | cámus | cámus- |

| nine | tə́wxʷ | tə́wxʷ-, tawíxʷ- |

| ten | pánačš | pánks-, pánkst- |

| Ex: | nákʼ- 'one' + -aw- 'linking letter' + =xan 'time' → nákʼušn 'once, one time' |

| kán- 'three' + -x- 'linking letter' + =panxʷ 'year' → kánxpanxʷ 'three years' |

Lexical Suffix Use vs. True Compounds

Compounds typically combine two full words to make a third word with its own unique meaning. Often, this new compounded meaning is slightly different from or more specific than the pure sum of its parts. The word ‘blackboard,’ for example, doesn’t actually refer to ‘a board that is black.’ It more specifically refers to ‘a flat thing that you can write on with chalk.’

So far, we’ve seen many instances where English would use a compound and Cowlitz Coast Salish uses a root plus a lexical suffix. For example, the word ‘backbone’ in English is a compound of the full word ‘back’ and the full word ‘bone.’ In Cowlitz Coast Salish, as we saw in the first list of examples, the word ‘backbone’ is created from a root plus a lexical suffix.

The main difference between a root + a lexical suffix and a true compound is that lexical suffixes can never stand on their own, whereas one or more elements of a true compound can stand on their own as a fully fledged word.

While the point of this section is to illustrate the unique ways in which Cowlitz Coast Salish forms words using lexical suffixes, we want to be clear that Cowlitz Coast Salish does also have compound words. For example, the verb sáʔəmx̣kʷu ‘make a cedar-root basket’ is a compound of sáʔ- ‘make’ (as in sáʔn ‘he made it’) and ʔə́mx̣kʷu ‘cedar-root basket.’

Similar to true compounds, sometimes combining a root and a lexical suffix gives us a different or more specific meaning than what the two parts mean on their own. For example, the word taxʷálʼšn means ‘buy shoes,’ but its individual parts are: tə́xʷ- ‘buy’ + -ál- ‘linking letter’ + =xan ‘foot.’

Glossary

This glossary defines some of the grammar terms you may see within entries as you navigate the dictionary. Any bolded word within a definition is defined elsewhere in this list. Terms are listed in alphabetical order.

ƛʼpúlmixq - Cowlitz Coast Salish

Adjective - A state of being that isn’t marked for aspect. An adjective can form the basis of sentence: qʷamáalʼm k (you are slow).

Affix - A morpheme that attaches to the beginning of the word, as a prefix, or the end of a word, as a suffix.

Article - In English, a/an, the, this, etc. When combined with a word or phrase, they don’t change its original meaning - for example, a car and the car still refer to the idea ‘car.’ In ƛʼpúlmixq, the most common articles are t, tit, c, cic, and ʔit. You’ll find these articles in some headwords, Inflected Forms, and Example Phrases. An article at the very beginning of a phrase can be removed or exchanged for another article without changing the phrase’s overall meaning.

Aspect - The framing of a verb with respect to duration. See Imperfective and Perfective for the two basic ƛʼpúlmixq aspects.

Causative - A type of verb that indicates the subject causes the object to do something. Some dictionary entries labeled as causative may not have an obvious causative meaning, but nonetheless take causative objects. (Abbreviation: CAUS)

Example Phrases - Combinations of two or more full words with distinct meanings, with or without additional articles, particles, etc. For example, wá t ʔaskʷácɬ (what is your name) is listed as an Example Phrase under the entry skʷácɬ (name).

First-person - See person.

Imperfective - An aspect that tells you the verb is continuing, ongoing, progressing, or unending. In most cases, imperfective verbs in this dictionary are translated as verbs with -ing - for example, syə́pawn is translated as “he is walking.” (Abbreviation: IMPV)

Inflected Forms - Usable forms of the headword that may or may not include extra word parts. Many of the Inflected Forms in this dictionary are defined, but these definitions are a work in progress and are subject to change. See the sections on affixes, articles, morphemes, and particles for the kinds of extra word parts that you may find in the Inflected Forms section.

Intransitive - A verb that is not directed towards anything; in other words, a verb without an object. (Abbreviation: INTR)

Morpheme - The basic building block of a word. For example, walk, -ed, and -ing are all morphemes in English. A hyphen on a morpheme indicates that the morpheme “isn’t ready yet,” and may need additional pieces in order to stand as a full word. For example, the ƛʼpúlmixq imperfective intransitive stem námaw- is not a usable form and requires a subject, but námawn is a usable verb since the hyphens of námaw- and -n close each other. Morpheme, word part, and word piece are interchangeable in this glossary.

Noun - A person, place, or thing. In ƛʼpúlmixq verbs and adjectives can become nouns. A noun can also be the basis of a sentence: síɬmx tit stiqíw (gelding horse, lit. “the horse is a male”).

Number - The grammatical category for how many things or people are being mentioned. For the two grammatical numbers used in ƛʼpúlmixq, see singular and plural.

Object - The person or thing that is acted upon by the subject of a verb. (Abbreviation: O)

In English, objects are words that change according to their person and number:

|

English Objects |

Singular |

Plural |

|

First-Person |

me |

us |

|

Second-Person |

you |

you, you all, y’all |

|

Third-Person |

him, her, it, them (sg.) |

them |

In ƛʼpúlmixq, objects are endings that change according to their person, number, and aspect.

Plain transitive objects:

|

ƛʼpúlmixq object pieces |

Imperfective |

Perfective |

||

|

Singular |

Plural |

Singular |

Plural |

|

|

First-Person |

-cal- |

-taw- |

-c |

-tawɬ |

|

Second-Person |

-ci- |

-ci |

||

|

Third-Person |

-t- |

-n |

-i-n-umx* |

|

*see plural

Causative objects:

|

ƛʼpúlmixq object pieces |

Imperfective |

Perfective |

||

|

Singular |

Plural |

Singular |

Plural |

|

|

First-Person |

-mal- |

-maw- |

-mx |

-mulɬ |

|

Second-Person |

-mi- |

-mi |

||

|

Third-Person |

-staw- / -y-* |

-x / -xʷ* |

-x-umx / -xʷ-umx* ** |

|

* Irregular form used by some verbs.

** see plural

Note that, while these suffixes are called causative object suffixes, they are also used for some verbs that don’t necessarily have an obvious causative meaning.

Perfective - An aspect that tells you a verb is finished, complete, or over. In most cases, perfective verbs in this dictionary are translated as verbs with -ed - for example, yə́pɬ is translated as “he walked.” (Abbreviation: PFV)

Person - The distinction made between participants in a speech event.

First-person - What speakers call themselves [I and we].

Second-person - What speakers call the people they’re addressing [you and you all].

Third-person - What speakers call people or things that aren’t in the conversation [she, he, it, they].

Plural - The grammatical feature of being two or more of something. Because words that are grammatically singular in ƛʼpúlmixq can refer to one or multiple things, plural marking is used to unambiguously refer to multiple things.(Abbreviation: pl)

Note for verbs: The morpheme -i-umx indicates third-person plural (they, them). Unlike the other person pieces it does not strictly refer to a subject or object; instead it ambiguously means both, depending on the context. Thus, námiɬumx means “They finished” because there’s no third-person singular object to be made plural. The form náminumx, on the other hand, can mean “They finished it” or “She finished them” as the plural meaning can work as a subject or object depending on the context. Additionally this piece is written as -i-umx because the -i- goes before the final letter of the original form, thus ʔit námɬ > ʔit námiɬumx; ʔit námn >ʔit náminumx.

Reconstruction - This word was respelled by Kinkade from an older source for consistency, since consistent spelling within a resource helps learners understand how a word was pronounced when it was last recorded. If the reconstruction is from TLC, it has been respelled by linguists working for The Language Conservancy alongside informed membership and employees of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe. If the reconstruction is uncertain, it is still informed by research but some of the letters could be incorrect.

Second-person - See person.

Singular - One single item. In ƛʼpúlmixq, nouns that are grammatically singular can have a plural meaning. (Abbreviation: sg)

Subject - The person or thing that causes or experiences an event, which could be a verb, noun, or adjective. (Abbreviation: S)

In English, subjects are words that change according to their person and number.

|

English Subjects |

Singular |

Plural |

|

First-Person |

I |

we |

|

Second-Person |

you |

you, you all, y’all |

|

Third-Person |

he, she, it, they (sg.) |

they |

In ƛʼpúlmixq, subjects are smaller pieces that attach to the end of the verb. They change according to their person, number, and aspect.

|

ƛʼpúlmixq subject pieces |

Imperfective |

Perfective |

||

|

Singular |

Plural |

Singular |

Plural |

|

|

First-Person |

-anx |

-stawt |

kn |

kɬ |

|

Second-Person |

-axʷ |

-alapt |

k |

kp |

|

Third-Person |

-n |

-iɬt |

-i-umx* |

|

*see plural

Note: The forms without a hyphen are separated from the verb by a space in actual writing (i.e. ʔit ɬə́x̣n kn, not ʔit ɬə́x̣nkn). As you’ve seen previously, perfective verbs can be used without any subject ending, since there's no ending to represent the perfective third-person singular subject. Also, the perfective subjects kn, k, kɬ, and kp can be used with adjectives and nouns (as in čtƛʼpúlmx kn 'I am a Lower Cowlitz person'), so they're more independent of the verb than other endings. This is why we write them with a space, as separate little words.

Third-person - See person.

Transitive - A verb that is directed towards someone or something; in other words, a verb with an object. (Abbreviation: TR) - See object for more details.

Verb - An action or state that can be perfective or imperfective. A verb can stand on its own as a full sentence: syə́pawn (“she is walking”).